A trip to the Ahart Herbarium at Chico State & a nine-mile trail run in Upper Bidwell Park

(and bonus amateur geologizing)

Early in November I drove from my home outside of Nevada City to Chico to volunteer for the first time at the Ahart Herbarium at Chico State University. The one hour and forty-five minute trip took me through a gradual shift from mixed conifer forest in the higher foothills of Nevada & Yuba Counties to blue oak savanna to expansive grassland in the valley. There’s a great view of the Sutter Buttes on the descent to Dobbins where you feel as though you’re looking down at their peaks from above.

When I arrived in Chico, I parked on the street off-campus and crossed my fingers that I wouldn’t get a ticket as I walked down Ivey Street to the Science Building only to find out that the Herbarium is in Holt Hall. On my walk over, I had the day’s first encounter with Big Chico Creek, crossing it on a footbridge with a pressure-treated deck. I noted immediately that the shady, wooded corridor would be a refuge in the intense valley heat of summer. I entered Holt Hall on the ground floor and went into the Herbarium to introduce myself to the curator, Lawrence. He introduced me to the other volunteers, including a woman who was also working on navigating a switch from the humanities into the world of botany. Lawrence and I talked a bit about the shape of his career and my goals before he gave me a tour of the Herbarium.

I had entered into the main working area—a large classroom with glass-windowed cabinets full of botany books taking up a whole wall, black counters jutting out from two of the other walls, a chalkboard on the fourth, and rows of lab tables with dissecting scopes. Lawrence showed me the back room, which holds the Herbarium’s collection in dozens of metal cabinets. Each is labeled like a library’s stacks—the plant family’s name (or range of families) with genus (or range of genera) found inside. An example: Apiaceae (Lomatium-Ozmorhiza). Lawrence told me that the collection is one of few still growing—receiving upwards of 2,500 specimens a year—and that space is at a premium in the cramped collection room. He hopes that compactors could be installed—like at the Jepson Herbarium at UC Berkeley—which would allow rows of cabinets to be stored flush against one another and then moved when one needs to be accessed.

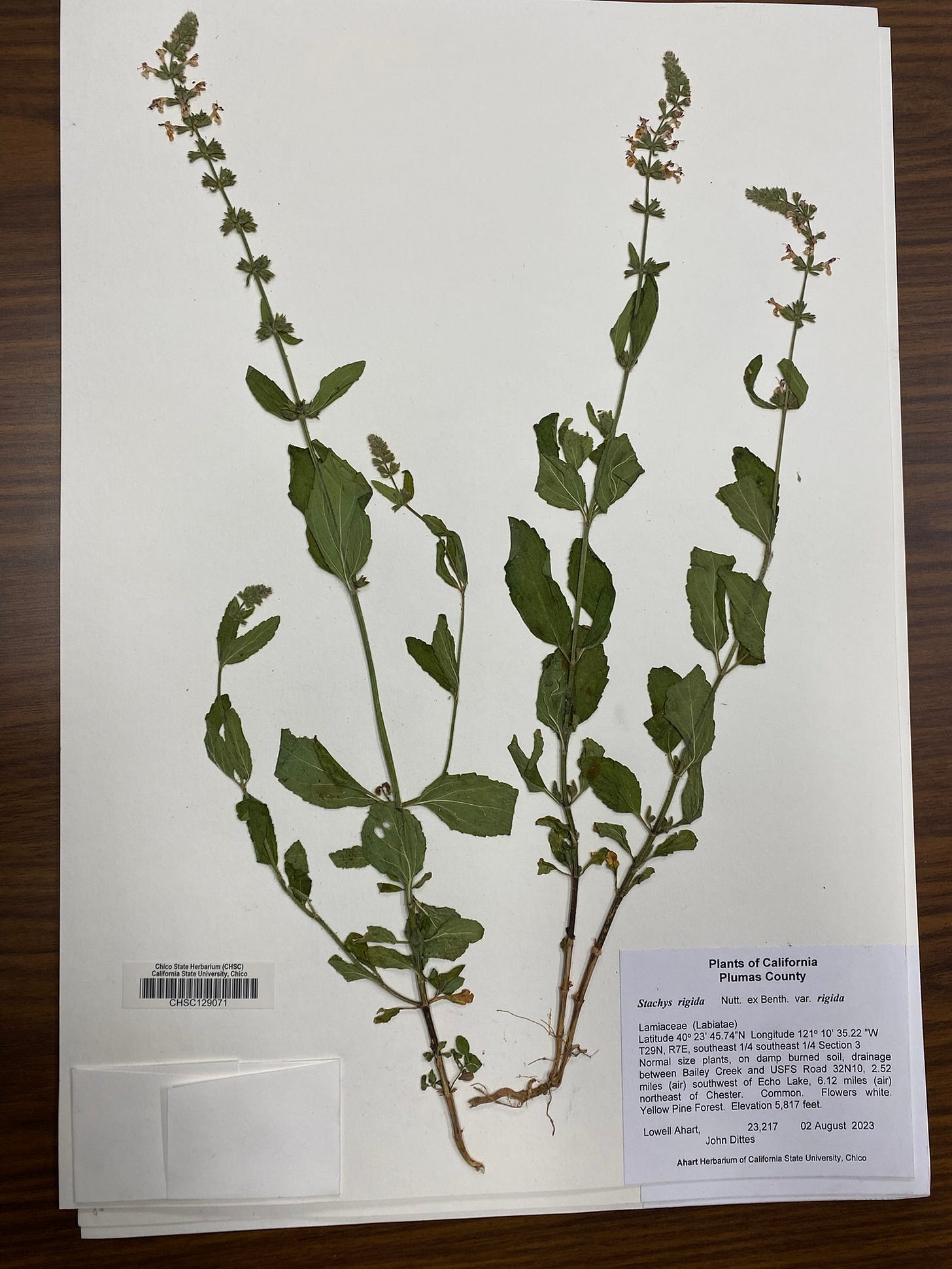

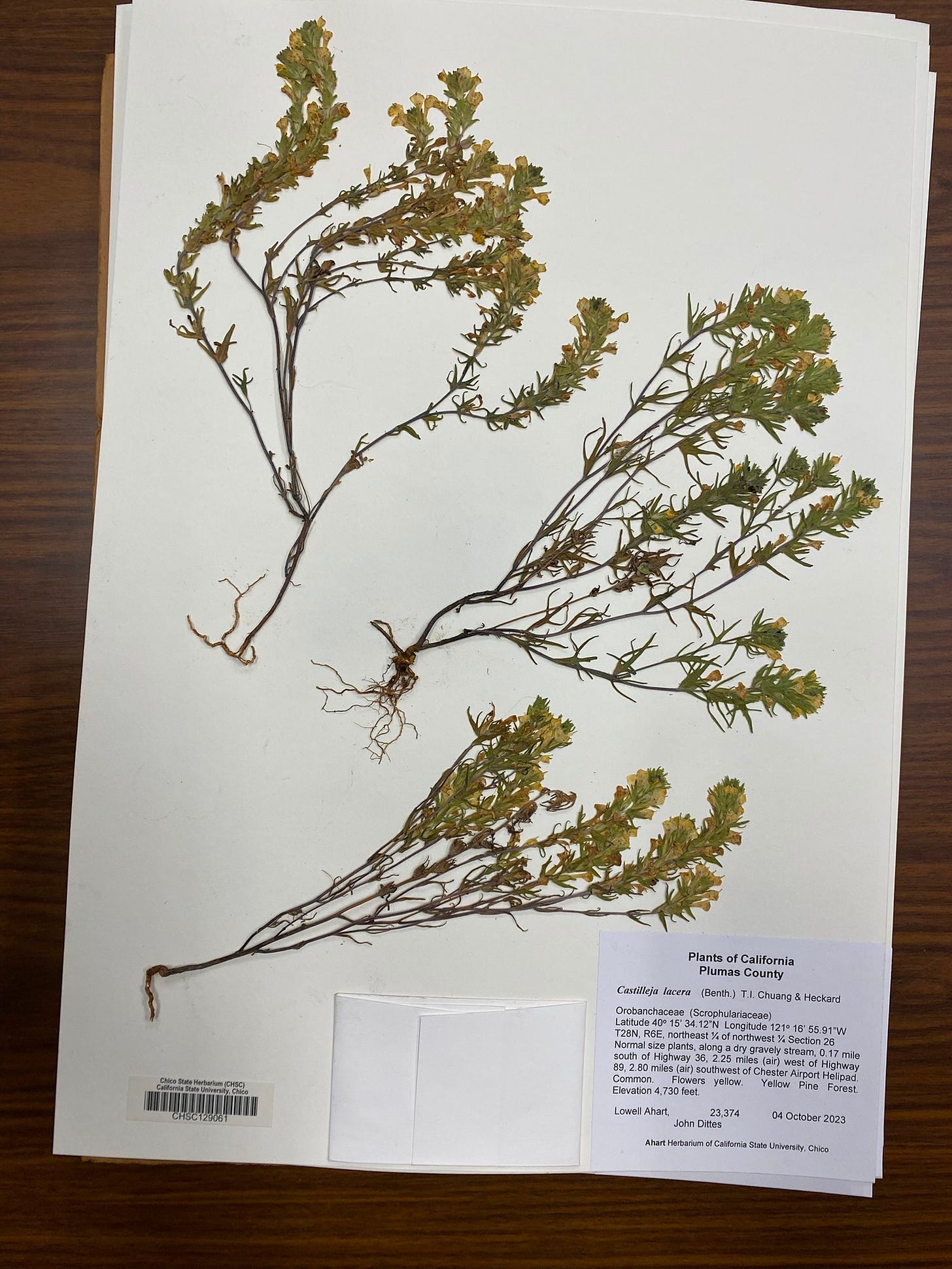

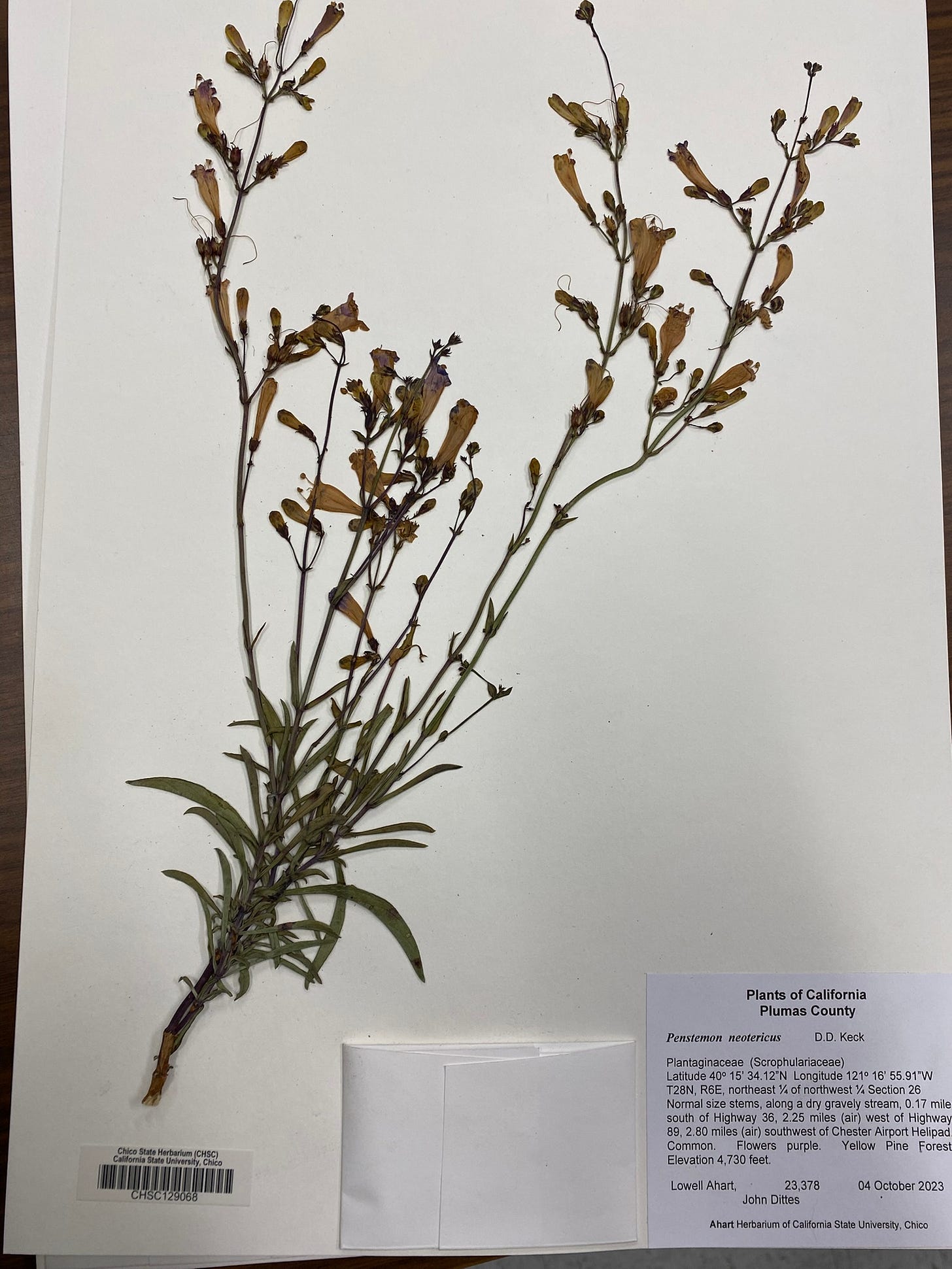

The first cabinet he opened was the Apiaceae one mentioned above and a strong smell like Norwegian shag tobacco wafted out from inside. Large folders held the plant specimens, which themselves are mounted on 11.5’’ by 16.5” sheets of paper. Lowell Ahart—the Herbarium’s benefactor and major collector—does the majority of the mounting at his ranch. Apparently, a life without TV or alcohol gives him the time to work slowly and with great intention in his gluing of plants onto the paper.

According to the university’s website, the Ahart Herbarium holds over 125,000 specimens, including over 21,000 collected by Ahart himself. The collection’s emphasis is on Northern California flora, and is the most complete repository of plant specimens from northeastern California. There are also cones, bryophytes, lichens, seaweeds, and slime molds in the collection.

After the tour, an older volunteer showed up with a ziploc bag full of plants for everyone to look at. Each was cradled in a damp paper towel, so he delicately unwrapped each specimen and placed them on one of the lab tables. We all huddled around and employed our senses to get to know the plants—including stinkwort (Dittrachia graveolens). He taught me two willows (Salix laevigata and S. goodingii) with the tip that they’re the only two willows with folded bud scales.

Lawrence set me up on a laptop and showed me how to enter new specimens into the Consortium of California Herbaria database. I put in a few hours of data entry, mostly plants collected by Lowell Ahart in Plumas County in 2023. I learned a few new families from the work, including Caryophyllaceae (the Pinks) and Potamogetonaceae (the Pondweeds). I kept a list of the binomial name, common name, and family of each specimen in my notebook and also took a picture of each after I had entered it into the database.

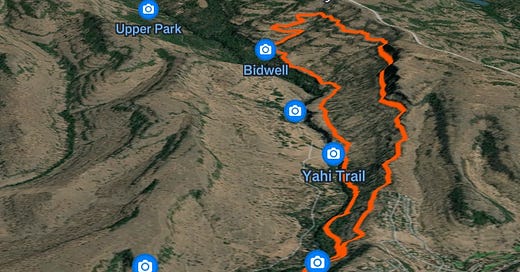

At 4 pm I put my stack away and said good-bye to Lawrence and the few volunteers who remained. I walked back to my car (no ticket!) and drove northwest to the Chico Canyon Trailhead at the base of the foothills outside of town. The sky threatened rain but I had a rain jacket stuffed in the back pocket of my hydration vest so I hit the trail with a loop route I’d found on Strava loaded onto my watch. The mist started as soon as I emerged from a small woods at the edge of the neighboring golf course—and it began to rain as I started climbing the weird Tuscan Formation rocks up to the Rim Trail. This three-million-year-old rock is volcanic conglomerate made up of layered ash, mudflows, and patches of alluvium—but what I saw with my untrained eye was volcanic bedrock with small holes like the air bubbles in good sourdough with big pieces of smooth river stone and other angular pieces of fractured rock inside of it.

As I climbed, I could see more and more of the Park Fire burn scar on the hills across Big Chico Creek. I made it to the Rim Trail as the rain picked up yet again, soaking through the rain coat I’d put on less than a mile into the run. I ran through a corridor of chaparral, bordered on both sides by dark volcanic outcroppings. About 5.5 miles in, the trail began switchbacking down to the grassland above the narrow canyon cut by the creek’s flow. Here I ran through the Park Fire burn scar for about a quarter mile or so—bare burned earth & scorched oaks. Wet soil gummed up my shoes.

After the descent, I joined back up with the Annie Bidwell Trail. I saw a medium-sized black bear, its fur all soaked and matted, cross the trail and head into the tall, dried-out annual grasses on the other side. The bear heard me galumphing down toward it and quickly decided to retreat back down into the Big Chico Creek canyon. I stopped where it must have climbed down the rocky cliffs to check out the geology: Lovejoy basalt—dark, pimply volcanic rock with steep cliffs on both sides and riparian vegetation tucked along the watercourse below.

I finished my nine miles and realized I’d been going too fast to get a good look at the landscape of the Big Chico Creek watershed—just little glimpses. I’d like to come back for a longer day hike later this winter with Kale—and do some botanizing in the spring. I have no idea what forbs are associated with this geology and I’m also curious what will pop up in the burn scar. I changed back into my dry clothes in the car and made the trip back to Nevada City in the pouring rain, returning to my own place with its ground saturated for the first time since spring.

Follow me on iNaturalist & Strava for more botanizing & trail running.

can't wait to keep reading more about your dive into the world of botany!